In the realm of intellectual property👉 Creations of the mind protected by legal rights. (IP), design rights serve as a crucial mechanism for safeguarding the aesthetic appeal and visual distinctiveness of products. For large corporations, understanding the precise scope of protection offered by design rights, and identifying the applicable subject matter, is paramount for building a robust IP portfolio and maintaining a competitive edge in global markets. This subpage delves into these fundamental aspects, providing a comprehensive overview for IP professionals and corporate strategists.

The protected subject matter: Defining a design

At its core, an industrial design, or simply a “design” in the context of design rights, refers to the ornamental or aesthetic aspect of an article. It is the visual appearance of a product or a part of a product, rather than its technical function, that is protected. This distinction is vital for corporations, as it clarifies which innovations fall under design protection versus patent👉 A legal right granting exclusive control over an invention for a limited time. protection.

A design may encompass a wide array of features, both three-dimensional and two-dimensional, including:

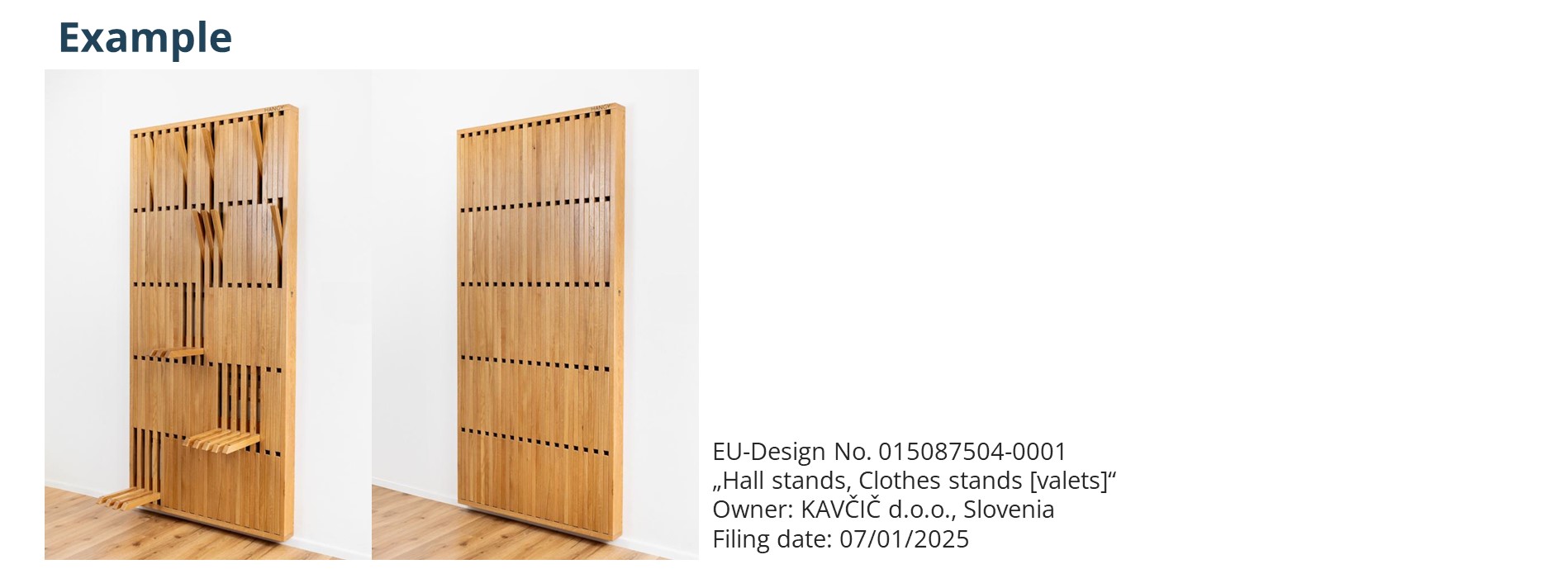

- Shape and Configuration: This refers to the three-dimensional form of an article. Examples range from the distinctive contour of a car body, the ergonomic shape of a smartphone, or the unique silhouette of a piece of furniture. The overall physical structure and how its various parts are arranged fall under this category.

- Pattern and Ornament: These are two-dimensional features applied to the surface of an article. This can include repetitive motifs on textiles, intricate engravings on jewelry, graphic prints on packaging, or decorative elements on consumer electronics.

- Color and Line: Specific color combinations or the arrangement of lines can also contribute to the overall visual impression of a design. While a single color is rarely protectable, a distinctive combination or a unique arrangement of lines forming a pattern can be.

- Texture and Material: The tactile quality and the inherent visual characteristics of the materials used can also be protectable elements if they contribute significantly to the overall aesthetic impression of the design. For instance, a specific wood grain pattern or a unique surface finish on a product.

Crucially, design rights can protect the appearance of an entire product or parts of an article. This flexibility allows corporations to tailor their protection strategy. For example, a company might protect the overall design of a new coffee machine, but also separately protect the unique design of its carafe or control panel if those elements possess distinct individual character and are likely targets for imitation. This granular approach is often critical for complex products with multiple distinctive components.

Beyond physical products, the scope of design protection has evolved to embrace digital and intangible assets. This includes:

- Graphic Symbols and Icons: The unique visual representation of icons used in software, mobile applications, or on product interfaces can be protected. Think of the distinctive app icons on a smartphone.

- Typography: While individual letterforms are generally not protectable, a unique and original typeface design can, in some jurisdictions, qualify for design protection due to its aesthetic qualities.

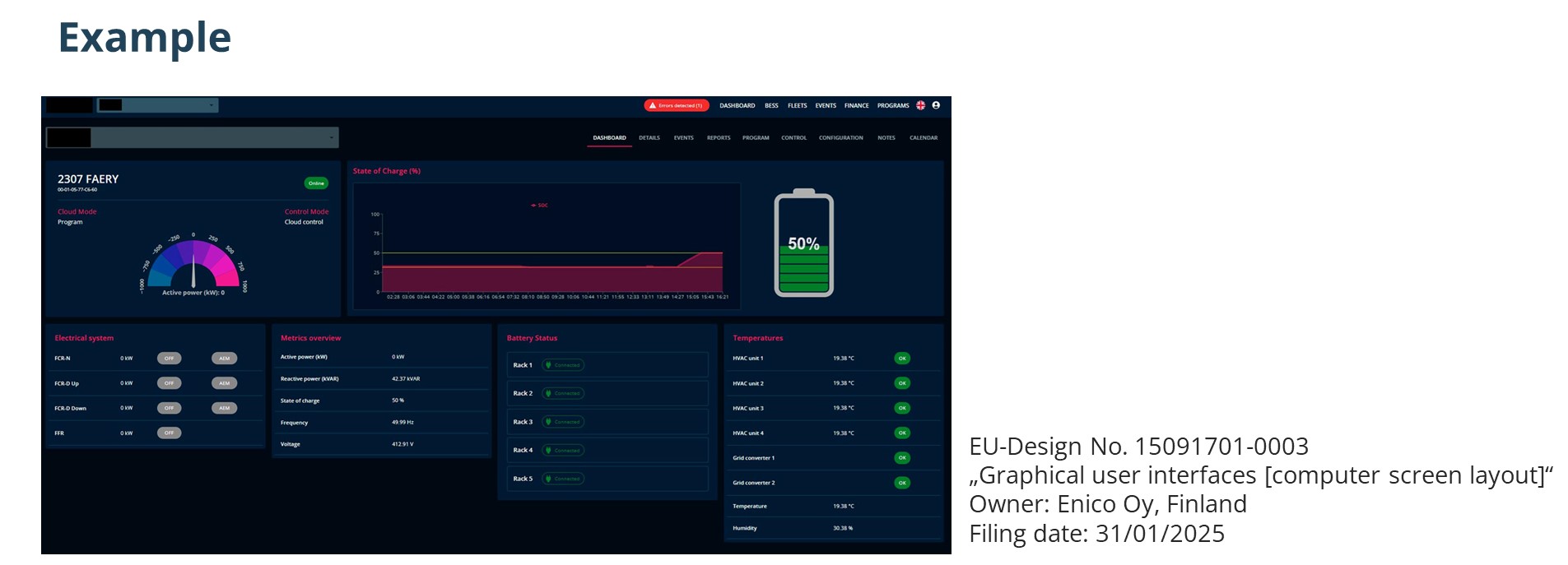

- Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs): The visual layout, arrangement of elements, and overall aesthetic of software interfaces, including interactive elements, menus, and screen displays, are increasingly recognized as protectable designs. This is particularly relevant for technology companies developing software, apps, and digital platforms where user experience is heavily influenced by interface design. The arrangement of buttons, color schemes, and visual cues can all contribute to the protectable design of a GUI.

Relevant fields of application and industry examples

Design rights are not confined to a single industry but are vital across a diverse spectrum of sectors where visual appeal and product differentiation are key competitive factors. For large corporations, leveraging design rights across their various product lines is a strategic imperative.

- Fashion and Textiles: This is perhaps one of the most intuitive applications. From the cut and silhouette of a garment to the unique patterns on fabrics, footwear, and accessories, design rights are fundamental for protecting seasonal collections and brand👉 A distinctive identity that differentiates a product, service, or entity. identity. Fast-fashion cycles often rely on unregistered design rights for quick, short-term protection, while iconic luxury designs benefit from registered protection.

- Furniture and Interior Design: The shapes of chairs, tables, lighting fixtures, and decorative objects are prime candidates for design protection. Companies like IKEA, Vitra, or Herman Miller heavily rely on design rights to protect their distinctive furniture lines and prevent imitations.

- Electronics and Consumer Goods: In a market saturated with similar functionalities, design becomes a critical differentiator. The sleek form factor of smartphones, the ergonomic design of household appliances (e.g., Dyson vacuum cleaners, KitchenAid mixers), and the aesthetic of smart home devices are frequently protected by design rights. Apple’s extensive portfolio of design patents for its iPhones and iPads is a prominent example of this strategic focus.

- Automotive Design: The exterior and interior aesthetics of vehicles, including specific components like headlights, grilles, dashboards, and wheel designs, are heavily protected. Automotive manufacturers invest massive resources in design, and design rights are essential to safeguard these investments and maintain brand recognition.

- Packaging Solutions: The shape, graphics, and overall appearance of product packaging can be highly distinctive and contribute significantly to brand recognition and consumer appeal. Iconic examples include the Coca-Cola bottle or unique perfume bottles. Design rights protect these visual elements, preventing competitors from mimicking a product’s distinctive presentation.

- Toys and Games: The visual appearance of toys, action figures, board game components, and even the unique interlocking system of building blocks (like LEGO) are protected by design rights. This ensures that the aesthetic appeal that attracts consumers remains exclusive to the creator.

- Digital Designs: As mentioned, the visual elements of software, applications, and websites are increasingly important. This includes the design of icons, user interfaces (GUIs), animated transitions, and even the layout of web pages. Companies like Microsoft, Google, and various app developers actively seek design protection for their digital interfaces to enhance user experience and maintain brand consistency across platforms.

Exclusions from protection: What design rights do not cover

While broad, design rights are not limitless. Understanding what cannot be protected is as important as knowing what can, particularly for large corporations navigating complex product development cycles. Key exclusions include:

- Features Solely Dictated by Technical Function: A design cannot be protected if its appearance is solely determined by the technical function it performs. For example, a basic screw head designed purely for its function of tightening would not be protectable as a design. The rationale is that such features are necessary for the product to work and should not be monopolized through design rights, as this would hinder technical innovation👉 Practical application of new ideas to create value.. However, if there are multiple ways to achieve the same technical function, and a designer chooses a particular aesthetic form, that form can be protected. The “could have been designed differently” test is often applied here.

- Features of Interconnection: Designs of features that must necessarily be reproduced in their exact form and dimensions in order to allow the product to be mechanically connected to or placed within another product are also generally excluded. This ensures interoperability👉 Systems' ability to exchange and use data seamlessly. and prevents monopolies on essential connection points (e.g., the shape of a USB plug).

- Ideas and Concepts: Design rights protect the specific visual manifestation of an idea, not the idea itself. A concept like “a comfortable chair” cannot be protected; only a chair with a particular, novel, and individual aesthetic design can be.

- Offensive or Immoral Designs: Designs contrary to public policy or accepted principles of morality are typically excluded from protection.

- Designs Lacking Novelty👉 Requirement that an invention must be new and not previously disclosed. or Individual Character: As discussed in the next section, if a design is not new or does not possess individual character, it will not qualify for protection.

Conditions for protection: Novelty and individual character

For a design to be eligible for protection, particularly under the European Union’s Registered Community Design (RCD) system, it must satisfy two fundamental substantive requirements: novelty and individual character. These criteria are assessed from the perspective of an “informed user,” a concept crucial for understanding the scope of protection.

Novelty

A design is considered new if no identical design has been made available to the public before the date of filing the application for registration (or the priority date, if applicable). A design is considered “identical” if its features differ only in immaterial details from an earlier design.

Key aspects of the novelty requirement:

- Prior Disclosure: Any disclosure of the design to the public before the filing date can destroy its novelty. This includes exhibition, marketing, publication, or commercial use anywhere in the world. Corporations must be extremely careful with public disclosures, such as product launches, press releases, or even internal presentations that might be accessible externally, before filing their design applications.

- Grace Period: Recognizing the realities of product development and marketing, many jurisdictions, including the EU, offer a “grace period.” In the EU, this is a 12-month period preceding the filing date (or priority date) during which the designer’s own disclosure of the design will not destroy its novelty. This allows companies to test market reception or make necessary adjustments before committing to a formal registration. However, it’s crucial to note that this grace period only applies to disclosures made by the designer or their successor in title, or as a consequence of an abuse in relation to the designer.

- Global Standard: Novelty is generally assessed on a global scale. A design disclosed anywhere in the world before the filing date can potentially invalidate a subsequent application. This necessitates thorough prior art searches for corporations operating internationally.

Individual character (or originality)

Beyond novelty, a design must possess individual character. A design has individual character if the overall impression it produces on the informed user differs from the overall impression produced on such a user by any design that has been made available to the public before the filing date.

Understanding the “informed user” is central to this criterion:

- The “Informed User”: This is not an average consumer, nor is it a technical expert. The informed user is someone who is particularly attentive to the product in question, has a certain degree of knowledge about the designs existing in the sector concerned, and is likely to make a direct comparison between the designs. They are more discerning than an average consumer but do not possess the expertise of a professional designer or manufacturer.

- Overall Impression: The assessment focuses on the “overall impression” created by the design, not just individual features. This means that minor differences in isolated elements may not be enough to establish individual character if the general aesthetic remains largely the same as a prior design. Conversely, a design may have individual character even if it incorporates known elements, provided their combination creates a novel overall impression.

- Designer’s Freedom: The degree of freedom the designer had in creating the design is taken into account. If the design field is highly constrained by technical function or existing designs (e.g., a standard bottle cap), even small differences might be sufficient to establish individual character. If the designer had a high degree of creative freedom, a more significant difference from prior designs would be required. This consideration is particularly relevant for corporations operating in mature markets with many existing designs.

For companies, proactively assessing novelty and individual character through comprehensive design searches and expert legal opinions before filing is a critical risk👉 The probability of adverse outcomes due to uncertainty in future events. mitigation strategy. While many design registration systems (like the RCD) do not conduct a substantive examination for these criteria prior to registration, these requirements are rigorously tested during invalidity proceedings or infringement👉 Unauthorized use or exploitation of IP rights. litigation. Therefore, ensuring a design genuinely meets these thresholds is paramount for the enforceability and value of the acquired right.

In conclusion, the scope of design protection is broad, encompassing both tangible product aesthetics and increasingly vital digital interfaces. For corporations, a deep understanding of what constitutes a protectable design, its applicable fields, and the critical requirements of novelty and individual character, is foundational to effectively leveraging design rights as a strategic asset.