The End of the Tall Corporate Ladder? Flattened Hierarchies and the Rise of Knowledge Workers

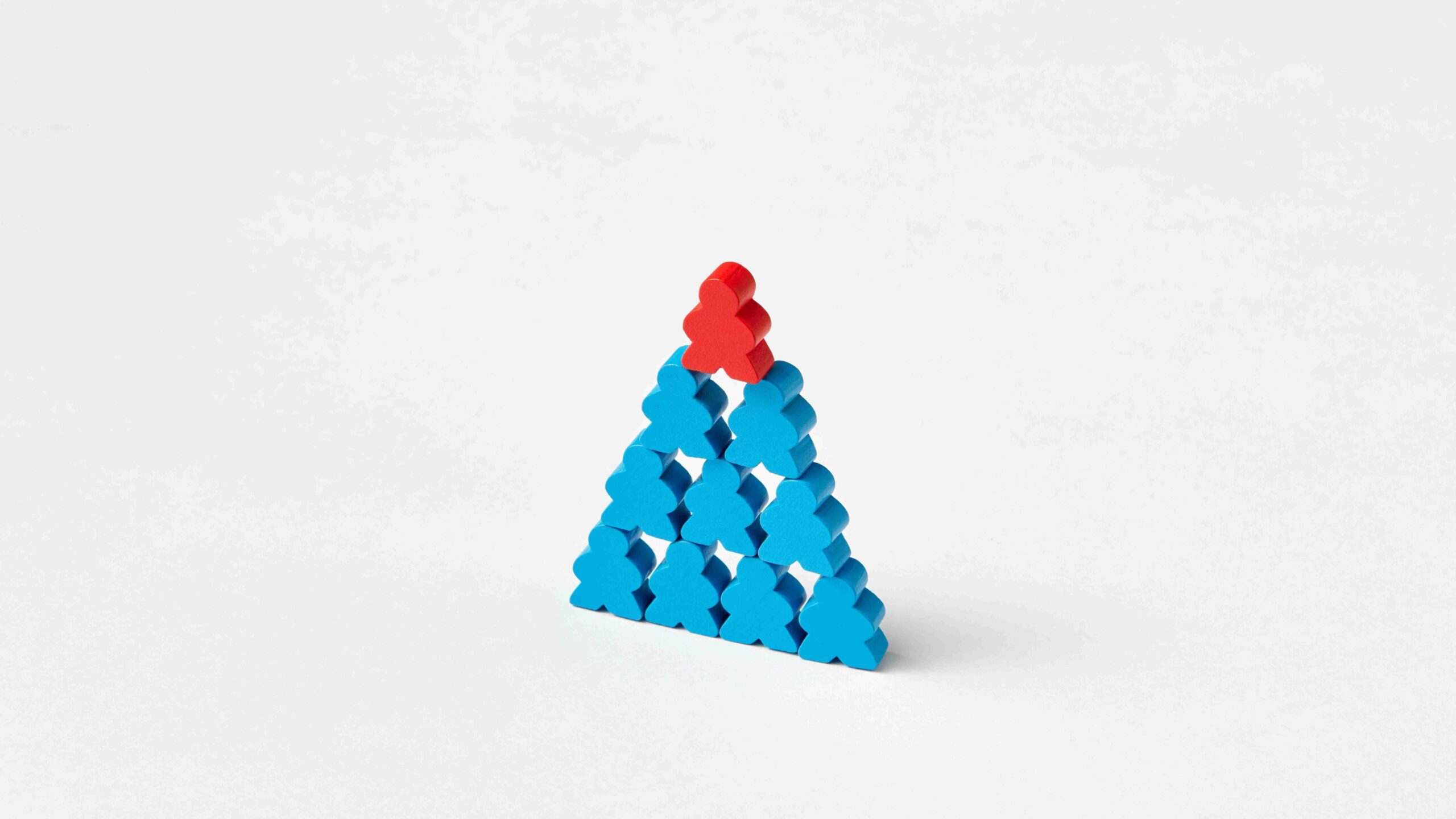

Modern firms are shifting from steep hierarchies to flattened structures as firm-specific human capital👉 Knowledge, skills, and abilities of individuals driving economic growth. becomes central to value creation. Traditional shareholder-centric governance models are being challenged by pluralistic approaches that recognize employees’ knowledge as a key asset. Flattened hierarchies enable faster decisions, greater autonomy, and better alignment with knowledge-intensive work. This shift calls for new governance frameworks that balance power, protect organizational rents, and support long-term value creation.

Chassagnon, Virgile, Hollandts, Cavier: Human capital and the pluralistic governance of the modern firm: The emergence of flattened hierarchies at work, Revie D’Economie Industrielle, 168 4E Trimestre 2019, 79-102.

Rethinking Who’s Really in Charge: How Firm-Specific Human Capital Is Flattening Corporate Hierarchies

In recent decades, the traditional structure of corporate organizations—long dominated by steep, command-and-control hierarchies—has come under increasing scrutiny. Emerging research in organizational economics and corporate governance indicates that a fundamental shift is underway: the rise of flattened hierarchies, especially in industries where firm-specific human capital is central to value creation. This evolution in organizational structure challenges the long-standing shareholder primacy model and invites a reconsideration of internal governance frameworks.

This article draws on insights from the work of Virgile Chassagnon and Xavier Hollandts (2019), whose paper “Human Capital and the Pluralistic Governance of the Modern Firm: The Emergence of Flattened Hierarchies at Work” offers a comprehensive theoretical account of how knowledge-based economies are reshaping firms from the inside out.

From Shareholder Primacy to Pluralistic Governance

The traditional model of corporate governance has largely centered on the agency theory👉 Study of conflicts and incentives between principals and agents. paradigm, wherein shareholders are seen as the primary stakeholders, and managers act as their agents. Under this framework, the firm’s main objective is the maximization of shareholder value. However, this view, grounded in a legal fiction of ownership, has been critiqued by legal scholars for its failure to recognize the firm as a legal entity separate from its shareholders.

This perspective has significant implications. When firms are viewed as nexuses of contracts, the role of non-shareholding contributors—especially employees—is marginalized in governance structures. Yet, modern firms increasingly rely on employees who possess firm-specific human capital, defined as knowledge, skills, and competencies uniquely developed within and for the organization (Mahoney & Kor, 2015). This resource, unlike physical capital, is inalienable and cannot be easily transferred, sold, or substituted.

The Strategic Role of Human Capital

As industries shift from physical asset dependence to knowledge-based value creation, human capital—and particularly firm-specific human capital—has become a central competitive asset. Employees invest time, effort, and cognitive resources into learning systems, cultures, and relationships that are unique to their organizations. As a result, their departure often leads to significant organizational costs and loss of embedded knowledge.

This creates a bilateral dependency. Just as employees depend on firms for resources and career growth, firms depend on key employees to sustain their strategic advantage. This mutual vulnerability produces what Chassagnon and Hollandts refer to as a de facto power dynamic. While shareholders and managers may hold de jure power through formal ownership and control rights, employees with high levels of firm-specific knowledge wield significant informal influence within the organization.

Rajan and Zingales (1998) describe this dynamic through the lens of access: employees who gain access to critical organizational resources, and whose human capital becomes specialized through interaction with those resources, acquire power that cannot be dismissed through traditional top-down management mechanisms.

Flattened Hierarchies as an Organizational Response

One of the most notable organizational consequences of the rise in firm-specific human capital is the emergence of flattened hierarchies. This structural shift is marked by:

- Broader spans of control, where managers oversee larger teams directly,

- Reduced vertical layering, with fewer levels between frontline employees and executive leadership, and

- Enhanced horizontal collaboration, often facilitated by technology and decentralized decision-making systems.

There is empirical support for this transformation, showing that the number of direct reports to CEOs has increased significantly since the 1980s, while the number of hierarchical layers has decreased. This trend, sometimes described as delayering, is especially pronounced in human capital–intensive sectors such as consulting, tech, and biotech.

The logic is straightforward: in firms where specialized knowledge and rapid decision-making are critical, traditional hierarchies slow down communication, hinder innovation👉 Practical application of new ideas to create value., and fail to adequately reflect the distributed nature of expertise.

Governance Beyond Ownership: The Mediating Hierarchy

Chassagnon and Hollandts argue for a pluralistic governance model, building on the team production theory. In this model, the firm is not a property of shareholders but a collaborative entity comprising multiple stakeholders—employees, managers, investors—who collectively contribute to value creation.

To coordinate and mediate between these often-competing interests, Blair and Stout propose the concept of the mediating hierarchy: a governance body (e.g., the board of directors) whose role is to serve the interests of the firm itself, rather than any particular stakeholder group. This board functions as an internal court of appeal, balancing claims and ensuring organizational coherence.

Such a model is well-suited to environments characterized by high levels of firm-specific investment. It offers a mechanism to protect organizational rents from opportunistic behavior, whether by dominant shareholders or powerful employees.

Incentives and Work Arrangements in Human Capital–Driven Firms

The shift toward flattened hierarchies is accompanied by a need to rethink incentive structures and human resource policies. Employees who invest heavily in firm-specific knowledge need assurances that their investments will be recognized and rewarded. As a result, organizations increasingly turn to idiosyncratic employment arrangements, including:

- Customized compensation packages,

- Employee share ownership plans,

- Personalized career development opportunities,

- Greater autonomy in project and role definition.

These mechanisms aim not only to retain top talent but also to enhance organizational commitment and psychological ownership. Such arrangements, while potentially creating internal disparities, can significantly boost performance when applied transparently and strategically. Moreover, the prevalence of such customized work conditions highlights the inadequacy of uniform management models in complex, knowledge-intensive environments.

Toward Democratic and Distributed Power Structures

Flattened hierarchies also raise critical questions about power distribution within firms. Traditional hierarchies rely on authority-based control. However, when knowledge—and thus power—is decentralized, firms must evolve to accommodate distributed leadership models.

This transformation parallels broader calls for industrial democracy and employee participation in governance. In France, for example, recent legislation (e.g., the PACTE law of 2019) has institutionalized employee representation on corporate boards. Similar trends in Germany and Scandinavia point to a growing acceptance of codetermination, where employees play a formal role in strategic decision-making.

Chassagnon and Hollandts advocate for a solar organizational model, where the executive team serves as a central hub, but influence radiates outward and flows more freely across the firm. This metaphor captures the shift from vertical command chains to more networked, agile, and responsive structures.

Conclusion: Redefining the Modern Firm

The transition from capital-intensive to human capital–intensive production has profound implications for corporate structure and governance. It challenges not only the shape of internal hierarchies but also the foundational assumptions about ownership, authority, and control.

Flattened hierarchies are not simply cost-cutting strategies or management fads. They represent a deeper structural response to the changing nature of value creation in contemporary firms. As knowledge becomes the primary driver of competitive advantage, firms must develop governance models that can attract, retain, and empower those who hold that knowledge.

A pluralistic and participatory approach to governance—anchored in team production theory and supported by flattened organizational structures—may offer the best path forward. Such models recognize the reciprocal dependencies between firms and their knowledge workers and offer institutional arrangements that can sustain cooperation, innovation, and long-term value creation.

In rethinking who is truly “in charge” of the modern firm, we uncover a reality in which power is no longer owned—it is earned, shared, and negotiated within the evolving fabric of organizational life.

Image by DS stories at Pexels